- por Mariel Vela

From the gallery window overlooking the street, a structure can be seen inside. An excess of visual protein—protuberances that feel soft to the touch yet appear rocky to the eye. Is it the materialization of a keloid feeling, or are keloids the feelings it awakens in me? A keloid is the residual tissue of a wound, whether intentional or accidental, that leaves a visible mark on the surface of the skin. The acne scars on my mother’s face or the pink, elliptical edge around my friend’s navel where there was once a piercing are adolescent drawings—reliefs of time lived.

The exhibition Sentimientos Queloides brings together the work of eleven artists invited to collaborate through the practice of drawing in a broad, even experimental sense. In the wall text, Yope Projects refers to drawing as a physical and/or virtual space, as an inhabitant, a parasitic space. Simply by looking around the room, the question of what we call drawing metamorphoses to the point that it no longer seems particularly important to ask it. What becomes relevant instead is letting one’s eyes move along the edge, like sliding a fingertip across a knee to remember having fallen off a bicycle.

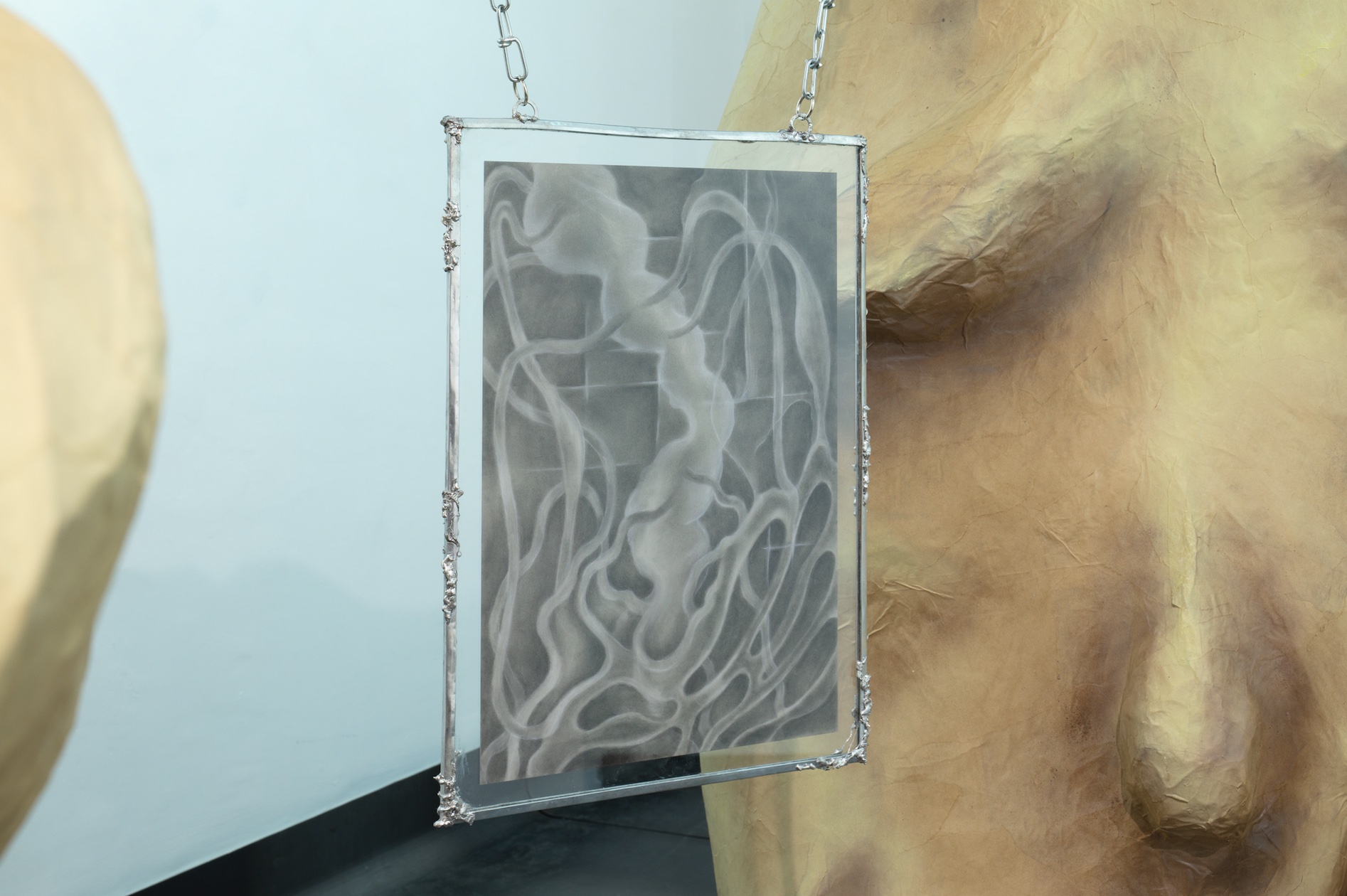

At the center stands Platelmintos by Sonia Bandura, suspended from a chain that seems to have emerged from its zinc frame. A form resembling a space-age tuber mimics the volumes of the caricature-like rock from which it hangs; there is a dignity to graphite as a material that I had never fully considered until now.

“There is no drawing that is not temporal, fragile, instantaneous, in a state of flux. You are looking, acting, and reacting while you think and feel, both analytically and instinctively. The drawing itself is simply the residue of such relationships,” says artist and writer Amy Sillman. To think of drawing solely as a preliminary practice or as the step preceding more important projects is to deny that state of flow generated by making without direction, by ruminating through lines and shadows. I have seen others draw absentmindedly, absorbed in the pleasure of invention.

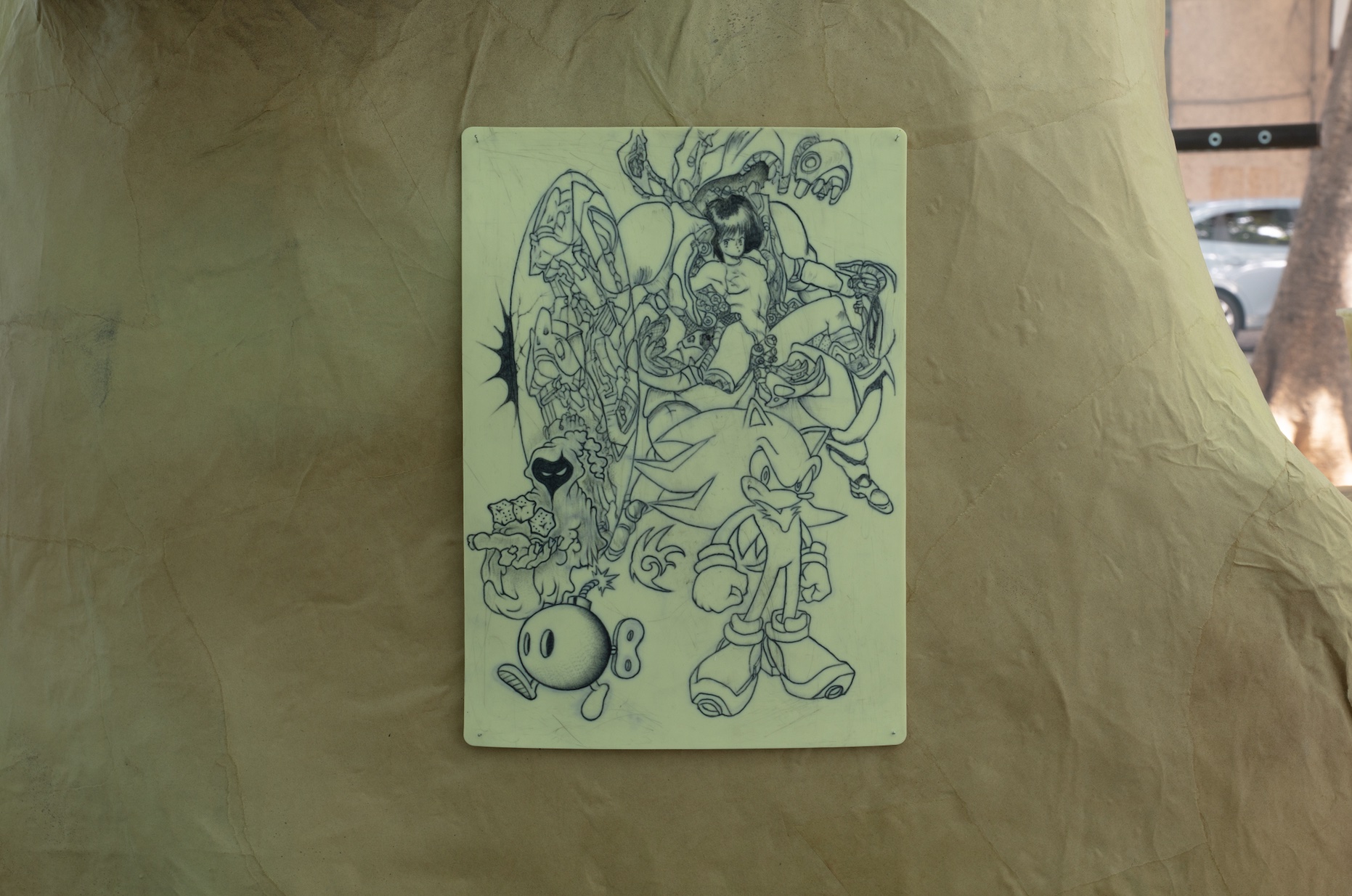

The pieces k99999 and k99999 (evil version) by Yope Projects are made with ink on synthetic skin and are at once like the Bic-pen drawings in my friends’ notebooks during class and the scribbled tattoos on thighs or on the forearm carved into a school desk. There’s Sonic, the mascot of the video game developer Sega Enterprises, and some manga characters I don’t recognize.

Nube sad I and Nube sad IV by Emilio Morales are UV prints on acrylic; mercury, quartz, or LED lights are used to dry the ink instead of heat, producing a dreamlike and slippery visual effect.

I look at the ink these clouds are made of, dried by artificial suns, and I can’t remember the last time I gazed at clouds searching for the shape of a little dog or a flying saucer—an activity that undoubtedly carries something melancholic.

Ángela Ferrari’s drawings are dreamscapes as well, perhaps embodied by the little pig sleeping peacefully—unaware that a greyhound hunts it or that it wanders, ruminating, along the white underside of a thicket. There is also the ostrich egg titled Wrought by Marián Roma, almost floating over a plain, medieval and domestic at once. On its calcium skin, an ejaculation, a dragon’s wing, and a heart are revealed.

Spontaneous generation is an obsolete hypothesis about the origin of life that holds that certain forms arise “spontaneously” from organic matter, inorganic matter, or a combination of both. It was never proven through the scientific method, but it was arrived at through visual evidence. In the exhibition Sentimientos Queloides, this hypothesis is no longer obsolete—I find myself believing once again in the emergence of forms, bringing themselves into being.

Published the 6th of July of 2024